MAJOR UPDATE

As of Fall 2021, this wiki has been discontinued and is no longer being actively developed.

All updated materials and announcements for the QCBS R Workshop Series are now housed on the QCBS R Workshop website. Please update your bookmarks accordingly to avoid outdated material and/or broken links.

Thank you for your understanding,

Your QCBS R Workshop Coordinators.

QCBS R Workshops

This series of 10 workshops walks participants through the steps required to use R for a wide array of statistical analyses relevant to research in biology and ecology. These open-access workshops were created by members of the QCBS both for members of the QCBS and the larger community.

The content of this workshop has been peer-reviewed by several QCBS members. If you would like to suggest modifications, please contact the current series coordinators, listed on the main wiki page

Workshop 5: Programming in R

Developed by: Johanna Bradie, Sylvain Christin, Ben Haller, Guillaume Larocque

Summary: This workshop focuses on basic programming in R. In this workshop, you will learn how to use control flow (for loops, if, while) methods to prevent code repetition, facilitate organization and run simulations. In addition, you will learn to write your own functions, and tips to program efficiently. The last part of the workshop will discuss packages that will not covered elsewhere in this workshop series, but that may be of interest to participants.

Link to new Rmarkdown presentation

Link to old Prezi presentation

Download the R script for this lesson:

Learning Objectives

- Learning what is control flow;

- Writing your first functions in R

- Speeding up your code

- Useful R packages for biologists

Control Flow

Program flow control can be simply defined as the order in which a program is executed.

Why is it advantageous to have structured programs?

- It decreases the complexity and time of the task at hand;

- This logical structure also means that the code has increased clarity;

- It also means that many programmers can work on one program.

This means increased productivity

Flowcharts can be used to plan programs and represent their structure

Representing structure

The two basic building blocks of codes are the following:

Selection

Program's execution determined by statements

if if else

Iteration

Repetition, where the statement will loop until a criteria is met

for while repeat

Decision making

if statement

if(condition) { expression }

if else statement

if(condition) { expression 1 } else { expression 2 }

What if you want to test more than one condition?

ifandif elsetest a single condition- You can also use

ifelsefunction to:- test a vector of conditions;

- apply a function only under certain conditions.

a <- 1:10 ifelse(a > 5, "yes", "no") a <- (-4):5 sqrt(ifelse(a >= 0, a, NA))

Nested if else statement

if (test_expression1) { statement1 } else if (test_expression2) { statement2 } else if (test_expression3) { statement3 } else { statement4 }

Challenge 1

Paws <- "cat" Scruffy <- "dog" Sassy <- "cat" animals <- c(Paws, Scruffy, Sassy)

1.- Use an if statement to print “meow” if Paws is a “cat”.

Beware of R’s expression parsing!

Use curly brackets {} so that R knows to expect more input. Try:

if (2+2) == 4 print("Arithmetic works.") else print("Houston, we have a problem.")

This doesn't work because R evaluates the first line and doesn't know that you are going to use an else statement

Instead use:

if (2+2 == 4) { #<< print("Arithmetic works.") } else { #<< print("Houston, we have a problem.") } #<<

Remember the logical operators

| == | equal to |

| != | not equal to |

| !x | not x |

| < | less than |

| < = | less than or equal to |

| > | greater than |

| >= | greater than or equal to |

| x & y | x AND y |

| x|y | x OR y |

| isTRUE(x) | test if X is true |

Iteration

Every time some operations have to be repeated, a loop may come in handy

Loops are good for:

- doing something for every element of an object

- doing something until the processed data runs out

- doing something for every file in a folder

- doing something that can fail, until it succeeds

- iterating a calculation until it converges

for loop

A for loop works in the following way:

for(val in sequence) { statement }

The letter i can be replaced with any variable name and the sequence can be almost anything, even a list of vectors.

# Try the commands below and see what happens: for (a in c("Hello", "R", "Programmers")) { print(a) } for (z in 1:30) { a <- rnorm(n = 1, mean = 5, sd = 2) print(a) } elements <- list(1:3, 4:10) for (element in elements) { print(element) }

In the example below, R would evaluate the expression 5 times:

for(i in 1:5) { expression }

In the example, every instance of m is being replaced by each number between 1:10, until it reaches the last element of the sequence.

for(m in 1:10) { print(m*2) }

for(m in 1:5) { print(m*2) }

for(m in 6:10) { print(m*2) }

x <- c(2,5,3,9,6) count <- 0 for (val in x) { if(val %% 2 == 0) { count = count+1 } } print(count)

For loops are often used to loop over a dataset. We will use loops to perform functions on the CO2 dataset which is built in R.

data(CO2) # This loads the built in dataset for (i in 1:length(CO2[,1])) { # for each row in the CO2 dataset print(CO2$conc[i]) # print the CO2 concentration } for (i in 1:length(CO2[,1])) { # for each row in the CO2 dataset if(CO2$Type[i] == "Quebec") { # if the type is "Quebec" print(CO2$conc[i]) # print the CO2 concentration } }

Tip 1. To loop over the number of rows of a data frame, we can use the function nrow()

for (i in 1:nrow(CO2)) { # for each row in the CO2 dataset print(CO2$conc[i]) # print the CO2 concentration }

Tip 2. If we want to perform operations on the elements of one column, we can directly iterate over it

for (p in 1:CO2$conc) { # for each row of the column "conc"of the CO2 df print(p) # print the p-th element }

Tip 3. The expression within the loop can be almost anything and is usually a compound statement containing many commands.

for (i in 4:5) { # for i in 4 to 5 print(colnames(CO2)[i]) print(mean(CO2[,i])) # print the mean of that column from the CO2 dataset }

for loops within for loops

In some cases, you may want to use nested loops to accomplish a task. When using nested loops, it is important to use different variables as counters for each of your loops. Here we used i and n:

for (i in 1:3) { for (n in 1:3) { print (i*n) } }

Getting good: using the ''apply()'' family

R disposes of the apply() function family, which consists of vectorized functions that aim at minimizing your need to explicitly create loops.

apply() can be used to apply functions to a matrix

(height <- matrix(c(1:10, 21:30), nrow = 5, ncol = 4)) } apply(X = height, MARGIN = 1, FUN = mean) ?apply

apply()

lapply() applies a function to every element of a list.

It may be used for other objects like dataframes, lists or vectors.

The output returned is a list (explaining the “l” in lapply) and has the same number of elements as the object passed to it.

SimulatedData <- list( SimpleSequence = 1:4, Norm10 = rnorm(10), Norm20 = rnorm(20, 1), Norm100 = rnorm(100, 5))

# Apply mean to each element ## of the list lapply(SimulatedData, mean) SimulatedData <- list(SimpleSequence = 1:4, Norm10 = rnorm(10), Norm20 = rnorm(20, 1), Norm100 = rnorm(100, 5)) # Apply mean to each element of the list lapply(SimulatedData, mean)

sapply()

sapply() is a ‘wrapper’ function for lapply(), but returns a simplified output as a vector, instead of a list.

The output returned is a list (explaining the “l” in lapply) and has the same number of elements as the object passed to it.

SimulatedData <- list(SimpleSequence = 1:4, Norm10 = rnorm(10), Norm20 = rnorm(20, 1), Norm100 = rnorm(100, 5)) # Apply mean to each element of the list sapply(SimulatedData, mean)

mapply()

mapply() works as a multivariate version of sapply().

It will apply a given function to the first element of each argument first, followed by the second element, and so on. For example:

lilySeeds <- c(80, 65, 89, 23, 21) poppySeeds <- c(20, 35, 11, 77, 79) # Output mapply(sum, lilySeeds, poppySeeds)

tapply()

tapply() is used to apply a function over subsets of a vector.

It is primarily used when the dataset contains dataset contains different groups (i.e. levels/factors) and we want to apply a function to each of these groups.

head(mtcars) # get the mean hp by cylinder groups tapply(mtcars$hp, mtcars$cyl, FUN = mean)

Challenge 2

You have realized that your tool for measuring uptake was not calibrated properly at Quebec sites and all measurements are 2 units higher than they should be.

1.- Use a loop to correct these measurements for all Quebec sites.

2.- Use a vectorisation-based method to calculate the mean CO2-uptake in both areas.

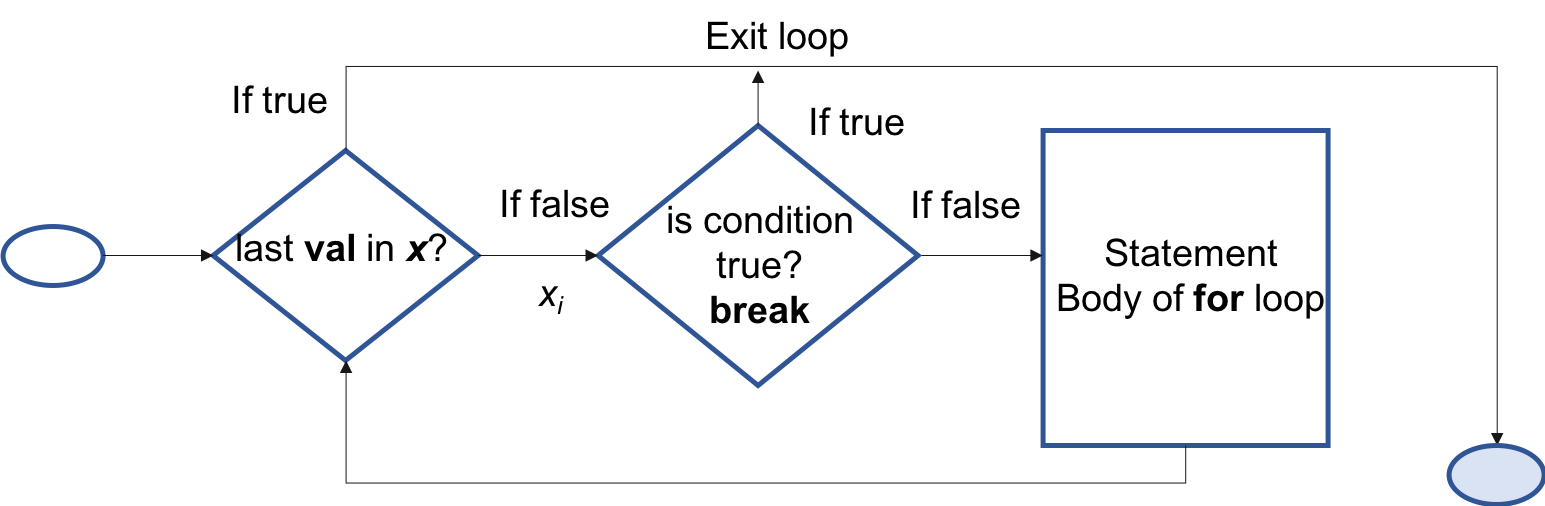

Modifying iterations

Normally, loops iterate over and over until they finish.

Sometimes you may be interested in breaking this behaviour.

For example, you may want to tell R to stop executing the iteration when it reaches a given element or condition.

You may also want R to jump certain elements when certain conditions are met.

For this, we will introduce break, next and while.

Modifying iterations: break

for(val in x) { if(condition) { break } statement }

Modifying iterations: next

for(val in x) { if(condition) { next } statement }

Print the CO2 concentrations for “chilled” treatments and keep count of how many replications were done.

count <- 0 for (i in 1:nrow(CO2)) { if (CO2$Treatment[i] == "nonchilled") next # Skip to next iteration if treatment is nonchilled count <- count + 1 # print(CO2$conc[i]) } print(count) # The count and print command were performed 42 times.

sum(CO2$Treatment == "nonchilled")

Modifying iterations: break

This could be equivalently written using a repeat loop and break

count <- 0 i <- 0 repeat { i <- i + 1 if (CO2$Treatment[i] == "nonchilled") next # skip this loop count <- count + 1 print(CO2$conc[i]) if (i == nrow(CO2)) break # stop looping } print(count)

Modifying iterations: while

This could also be written using a while loop:

i <- 0 count <- 0 while (i < nrow(CO2)) { i <- i + 1 if (CO2$Treatment[i] == "nonchilled") next # skip this loop count <- count + 1 print(CO2$conc[i]) } print(count)

Challenge 3

You have realized that your tool for measuring concentration did not work properly.

At Mississippi sites, concentrations less than 300 were measured correctly, but concentrations equal or higher than 300 were overestimated by 20 units!

Your mission is to use a loop to correct these measurements for all Mississippi sites.

Tip. Make sure you reload the data so that we are working with the raw data for the rest of the exercise:

data(CO2)

Edit a plot using for and if

Let's plot uptake vs concentration with points of different colors according to their type (Quebec or Mississippi) and treatment (chilled or nonchilled).

plot(x = CO2$conc, y = CO2$uptake, type = "n", cex.lab=1.4, xlab = "CO2 concentration", ylab = "CO2 uptake") # Type "n" tells R to not actually plot the points. for (i in 1:length(CO2[,1])) { if (CO2$Type[i] == "Quebec" & CO2$Treatment[i] == "nonchilled") { points(CO2$conc[i], CO2$uptake[i], col = "red") } if (CO2$Type[i] == "Quebec" & CO2$Treatment[i] == "chilled") { points(CO2$conc[i], CO2$uptake[i], col = "blue") } if (CO2$Type[i] == "Mississippi" & CO2$Treatment[i] == "nonchilled") { points(CO2$conc[i], CO2$uptake[i], col = "orange") } if (CO2$Type[i] == "Mississippi" & CO2$Treatment[i] == "chilled") { points(CO2$conc[i], CO2$uptake[i], col = "green") } }

Challenge 4

Generate a plot of showing concentration versus uptake where each plant is shown using a different point.

Bonus points for doing it with nested loops!

Writing functions

Why write functions?

Much of the heavy lifting in R is done by functions. They are useful for:

- Performing a task repeatedly, but configurably;

- Making your code more readable;

- Make your code easier to modify and maintain;

- Sharing code between different analyses;

- Sharing code with other people;

- Modifying R’s built-in functionality.

What is a function?

Syntax of a function

function_name <- function(argument1, argument2, ...) { expression... # What we want the function to do return(value) # Optional }

Arguments of a function

function_name <- function(argument1, argument2, ...) { expression... return(value) }

Arguments are the entry values of your function and will have the information your function needs to be able to perform correctly.

A function can have between 0 and an infinity of arguments. See the following example:

operations <- function(number1, number2, number3) { result <- (number1 + number2) * number3 print(result) } operations(1, 2, 3)

Challenge 5

Using what you learned previously on flow control, create a function print_animal that takes an animal as argument and gives the following results:

print_animal <- function(animal) { if (animal == "dog") { print("woof") } else if (animal == "cat") { print("meow") } } Scruffy <- "dog" Paws <- "cat" print_animal(Scruffy) print_animal(Paws)

Default values in a function

Arguments can also be optional and be provided with a default value.

This is useful when using a function with the same settings, but still provides the flexibility to change its values, if needed.

operations <- function(number1, number2, number3 = 3) { result <- (number1 + number2) * number3 print(result) } operations(1, 2, 3) # is equivalent to operations(1, 2) operations(1, 2, 2) # we can still change the value of number3 if needed

Argument ''...''

The special argument … allows you to pass on arguments to another function used inside your function. Here we use … to pass on arguments to plot() and points()

plot.CO2 <- function(CO2, ...) { #<< plot(x=CO2$conc, y=CO2$uptake, type="n", ...) #<< for (i in 1:length(CO2[,1])){ if (CO2$Type[i] == "Quebec") { points(CO2$conc[i], CO2$uptake[i], col = "red", type = "p", ...) #<< } else if (CO2$Type[i] == "Mississippi") { points(CO2$conc[i], CO2$uptake[i], col = "blue", type = "p", ...) #<< } } } plot.CO2(CO2, cex.lab=1.2, xlab="CO2 concentration", ylab="CO2 uptake") #<< plot.CO2(CO2, cex.lab=1.2, xlab="CO2 concentration", ylab="CO2 uptake", #<< pch=20) #<<

The special argument … allows you to input an indefinite number of arguments.

sum2 <- function(...){ #<< args <- list(...) #<< result <- 0 for (i in args) { result <- result + i } return (result) } sum2(2, 3) #<< sum2(2, 4, 5, 7688, 1) #<<

Return values

The last expression evaluated in a function becomes the return value.

myfun <- function(x) { if (x < 10) { 0 } else { 10 } } myfun(5) myfun(15)

function() itself returns the last evaluated value even without including return() function.

It can be useful to explicitly return() if the routine should end early, jump out of the function and return a value.

simplefun1 <- function(x) { if (x<0) return(x) }

Functions can return only a single object (and text). But this is not a limitation because you can return a list containing any number of objects.

simplefun2 <- function(x, y) { z <- x + y return(list("result" = z, "x" = x, "y" = y)) }

simplefun2(1, 2)

Challenge 6

Using what you have just learned on functions and control flow, create a function named bigsum that takes two arguments a and b and:

Returns 0 if the sum of a and b is strictly less than 50;

Else, returns the sum of a and b

Accessibility of variables

It is essential to always keep in mind where your variables are, and whether they are defined and accessible:

Variables defined *inside* a function are not accessible outside of it!

Variables defined *outside* a function are accessible inside. But it is NEVER a good idea, as your function will not function if the outside variable is erased.

var1 <- 3 # var1 is defined outside our function vartest <- function() { a <- 4 # 'a' is defined inside print(a) # print 'a' print(var1) # print var1 } a # we cannot print 'a' as it exists only inside the function vartest() # calling vartest() will print a and var1 rm(var1) # remove var1 vartest() # calling the function again doesn't work anymore

Use arguments then!

Also, inside a function, arguments names will take over other variable names.

var1 <- 3 # var1 is defined outside our function vartest <- function(var1) { print(var1) # print var1 } vartest(8) # Inside our function var1 is now our argument and takes its value var1

Be very careful when creating variables inside a conditionnal statement as the variable may never have been created and cause (sometimes unperceptible) errors.

It is good practice to define variables outside the conditions and then modify their values to avoid any problem

a <- 3 if (a > 5) { b <- 2 } a + b

If you had b already assigned in your environment, with a different value, you could have had a *bigger* problem!

No error would have been shown and a + b would have meant another thing!

Good programming practices

Why should I care about programming practices?

- To make your life easier;

- To achieve greater readability and makes sharing and reusing your code a lot less painful;

- To reduce the time you will spend to understand your code.

Pay attention to the next tips!

Keep a clean and nice code

Proper indentation and spacing is the first step to get an easy to read code:

- Use spaces between and after you operators

- Use consistently the same assignation operator. ← is often preferred. = is OK, but do not switch all the time between the two

- Use brackets when using flow control statements:

- Inside brackets, indent by *at least* two spaces;

- Put closing brackets on a separate line, except when preceding an `else` statement.

- Define each variable on its own line.

This code is not spaced, and therefore hard to read. All brackets are badly aligned, and it looks “messy”.

a<-4;b=3 if(a<b){ if(a==0)print("a zero")}else{ if(b==0){print("b zero")}else print(b)

This looks more organized, no?

a <- 4 b <- 3 if(a < b){ if(a == 0) { print("a zero") } } else { if(b == 0){ print("b zero") } else { print(b) } }

Use functions to simplify your code

Write your own function:

1.- When portion of the code is repeated more than twice in your script;

2.- If only a part of the code changes and includes options for different arguments.

This would also reduce the number of potential errors done by copy-pasting, and the time needed to correct them.

Let's modify the example from Challenge #3 and suppose that all CO2 uptake from Mississipi plants was overestimated by 20 and Quebec underestimated by 50. We could write this:

for (i in 1:length(CO2[,1])) { if(CO2$Type[i] == "Mississippi") { CO2$conc[i] <- CO2$conc[i] - 20 } } for (i in 1:length(CO2[,1])) { if(CO2$Type[i] == "Quebec") { CO2$conc[i] <- CO2$conc[i] + 50 } }

Or this:

recalibrate <- function(CO2, type, bias){ for (i in 1:nrow(CO2)) { if(CO2$Type[i] == type) { CO2$conc[i] <- CO2$conc[i] + bias } } return(CO2) }

newCO2 <- recalibrate(CO2, "Mississipi", -20) newCO2 <- recalibrate(newCO2, "Quebec", +50)

Use meaningful names for functions

Same function as before, but with vague names

rc <- function(c, t, b) { for (i in 1:nrow(c)) { if(c$Type[i] == t) { c$uptake[i] <- c$uptake[i] + b } } return (c) }

Use comments

Add comment to describe what your code does, how to use its arguments or a detailed step-by-step description the function.

# Recalibrates the CO2 dataset by modifying the CO2 uptake concentration # by a fixed amount depending on the region of sampling # Arguments # CO2: the CO2 dataset # type: the type ("Mississippi" or "Quebec") that need to be recalibrated. # bias: the amount to add or remove to the concentration uptake recalibrate <- function(CO2, type, bias) { for (i in 1:nrow(CO2)) { if(CO2$Type[i] == type) { CO2$uptake[i] <- CO2$uptake[i] + bias } } return(CO2) }